Cannabis in Canada: Who wins and who loses under new law

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCanada has become the second nation to fully legalise recreational cannabis. The end of prohibition means Canadian adults will be able to purchase and consume the drug from federally licensed producers.

The country has one of the highest rates of cannabis use in the world, particularly among young people.

Canadians spent an estimated C$5.7bn ($4.6bn; £3.5bn) in 2017 alone on combined medical and recreational use - about $1,200 per user. The bulk of that spending was on black market marijuana.

Uruguay was the first country to legalise recreational marijuana, although Portugal and the Netherlands have decriminalised the drug.

Here's a look at some of the consequences of this sweeping transition in Canada - and the potential winners and losers.

Lawyers - winners

Expect plenty of cannabis-related cases in the courts in the coming years.

"While we're moving away from a regime of prohibition, we're at the same time moving towards a very detailed framework of regulation," says Bill Bogart, a Toronto-based legal expert on drugs and legalisation.

And that means lots of regulatory details and grey areas for interest groups to challenge or exploit.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOne key issue will be how officers assess drug-impaired drivers compared to drink-drivers. And the reliability of technology used to detect THC, the psychoactive compound in cannabis, is already being challenged.

Some police forces have also opted out a roadside saliva testing device authorised by the federal government over cost concerns and the fact it might have problems working in colder weather.

Mr Bogart also predicts challenges to rules on edible cannabis products, which will not be legal for at least another year, as well as employment issues such as medical cannabis in the workplace.

Landlords - losers

The ending of prohibition means it is legal to consume cannabis and, under federal law, grow limited quantities at home.

Landlords are worried about smoke-related nuisances and damages arising from personal cultivation.

In one pre-emptive strike, a major landlord in Alberta said in September it would bar smoking and growing in all its buildings.

Provinces set the rules over where a person can consume cannabis, which has created a patchwork of regulations across the country.

In Ontario, for example, a person will be allowed to smoke cannabis wherever tobacco is allowed.

Public consumption will be prohibited in New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Saskatchewan, so some tenants may find themselves severely restricted in where they can use the drug.

Global brands - winners

The cannabis market is expected to be big business - and big business isn't shying away from investing as stigma fades around the drug's use.

Analysts suggest the size of the consumer pot market will be anywhere from $4.2bn to $8.7bn with between 3.4m and 6m people using cannabis recreationally in the first year after legalisation.

Those kind of numbers have sparked interest from major corporate players.

Reuters

ReutersCoca-Cola is keeping an eye on "the growth of non-psychoactive cannabidiol as an ingredient in functional wellness beverages" and had exploratory talks with Canadian licensed producer Aurora Cannabis about developing marijuana-infused beverages.

Corona beer owner Constellation Brands is investing with Canopy Growth to capitalise on growing demand for the drug by producing a non-alcoholic cannabis-based beverage.

Like Canopy and Aurora, other major publicly traded licensed producers have been building new facilities and ramping up production in earnest ahead of legalisation.

'Craft' cannabis producers - losers?

Where will small-scale cultivators fit into the market alongside big licensed producers and their soaring stock prices?

Advocates say ensuring that so-called craft producers can supply the market will curb illegal production and help secure an adequate retail supply of recreational cannabis.

But they still face obstacles, from financing to restrictions around land use and zoning.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome small producers have limited licenses to grow medical cannabis but have also been supplying the black or so-called "grey" market.

In an effort to promote a diverse cannabis marketplace, Canada has created specific "micro-cultivator" and "micro-processing" licenses.

The government is also toying with issuing licenses to people with minor nonviolent cannabis charges.

Cannabis researchers - winners

There is still a lot to learn about the impact of cannabis on the human body.

Research into medical and recreational cannabis use has long been hamstrung in Canada due to marijuana's status as a controlled substance, even though medical marijuana has been legal since 2001.

Funding was hard to come by, access to cannabis for research was restricted, and much of the research being done focused on the dangers of the drug.

Now, there are signs its new status will boost research and investment into studies looking at both the benefits and the harms of cannabis use, such as the impact of cannabis on issues like mental health, neurodevelopment, pregnancy, the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder, driving, and pain management.

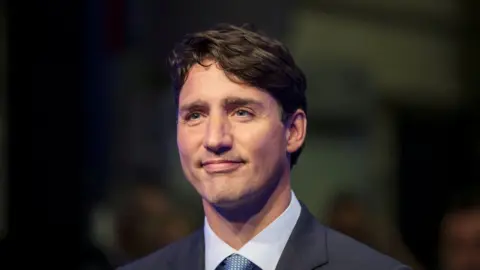

Justin Trudeau - winner

On the campaign trail in 2015, Justin Trudeau vowed that a Liberal government would get to work "right away" on a policy to legalise and regulate the sale of marijuana.Three years later, he can mark it as a promise kept.

He defends the move by saying it will protect young Canadians and prevent criminals from reaping the profits of the black market. But arguments continue to rage on the social cost and the health and safety risks.Meanwhile, the nitty-gritty of regulation has been left up to provincial and municipal leaders to figure out, a daunting task that has left many local politicians frustrated.

Reuters

Reuters

Canada's cities - losers?

Canadian cities say they are on the front lines of marijuana legalisation.

They will bear part of the responsibility for policing the new regime as well as for managing things like zoning, retail locations, home cultivation, business licensing and regulations around public consumption.

But many cities say they have yet to hear how federal taxes collected on cannabis sales will trickle down.

Some cities have also chosen to opt-out of allowing legal pot shops in their districts altogether.

The federal government projects it will raise $400m a year in tax revenues on the sale of cannabis. In a deal reached with the provinces, the feds will keep 25% of tax revenues up to an annual limit of $100m.

The rest will go to the provinces, which in turn will give funding to cities.