Voters’ Guide to

2020 U.S. Presidential Candidates on Cannabis Issues

1. Foreword by the study’s sponsor

As a purveyor of goods used in conjunction with cannabis, my livelihood, as well as those of my employees, hinges on a single public policy issue: cannabis.

So I was curious to find out not only where the candidates stood on making it legal, but also where they stood on allowing it to thrive as an industry. The gap between federal and state law has reached crisis level, and American businesses that could expand overnight are constrained by capital because banks risk losing their national charters should they abet the sale of what is still classified as a Schedule 1 narcotic.

This inconsistent legislative patchwork affects both recreational and medical users. In many states, it is perfectly legal for a doctor to prescribe cannabis for chronic pain, epilepsy, or any number of other conditions – unless the patient is being seen under the auspices of a federal program. These treatments that are becoming so pervasive now can still be withheld at facilities run by the Veterans’ Administration, and can cause terminally ill residents of federally subsidized housing to be evicted from their homes.

In states where cannabis is now legal – more than half of them – there are still “low-level pot dealers” stuck in prison under obsolete sentencing mandates.

The time has come to elect a president who will, while performing other duties and balancing competing interests, establish a nationwide standard for cannabis as a legal substance, distributed through a regulated industry with access to capital markets, with pardons and reparations considered for those who found themselves ahead of the law.

So I went about the task of educating myself about the various 2020 presidential candidates and their positions. I looked for a single point of reference that clarified each one’s stances and accomplishments in the cannabis space.

I couldn’t find it. I don’t think it existed until today. So I am thrilled to hand this narrative over to journalist William Freedman, whom I commissioned to sort out what nearly 30 individuals have been saying – and more importantly doing – about moving cannabis forward in America.

For the record, my vote remains uncommitted even after having read the following. My political agenda does not extend to supporting any individual. My purpose is to support the growth of the cannabis industry and to provide clear, factual data to cannabis voters.

I hope you enjoy this work and find it informative.

Regards,

Kevin Frija

CEO, VPR Brands, LP

2. Executive Summary

According to the newly established VPR Brands Guide, Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (D-HI) would be the best candidate for a single-issue cannabis voter to support in the 2020 presidential race. Her score – which combined her legislative leadership, positions stated, other actions taken, and willingness to emphasize her support for cannabis issues during the current campaign – exceeded those of runner-up Sen. Michael Bennet (D-CO) and third-place candidate Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ).

The highest-ranking non-legislator was former Alaska senator Mike Gravel, who now serves as CEO of a cannabis company and emphasizes his support for the industry more prominently than any other candidate. He is followed at that tier by a tie between former Massachusetts governor William Weld, the highest-rated Republican on cannabis issues, and former Colorado governor John Hickenlooper.

Headline results are summarized in Figure 7 under “Findings and Rankings: Weighted Score”.

3. Introduction

The 2020 presidential election is the first in which candidates find themselves, willingly or not, taking controversial public positions on cannabis issues.

This is because the culture has been changing drastically over the past decade when it comes to:

- acceptance of CBD and THC for both medical and recreational use,

- recognition that the laws prohibiting their sale and possession might be disproportionate to the harm to society,

- acquiescence in one-time tobacco-growing states that industrial hemp could serve as a replacement cash crop, and

- realization that no business can be fully legitimized until banks can provide it financing without fear of losing their federal charters.

Impetus for this report

We are in the midst of a wave of state-by-state victories – and a few state-by-state defeats – for those who seek to legalize cannabis. The challenge remains that the federal government – whether there was a one-party rule under the Republicans, one-party rule under the Democrats or any permutation of divided government – has maintained policies at odds with those of an ever-increasing roster of states. The time has come for clarity, and that can only come from a reexamination of cannabis policy at the federal level.

This moment coincides with a particularly frothy number of individuals who have decided to run for the presidency in 2020. In an election cycle where it will be difficult to break through with a message that resonates with voters and is yet significantly different from the dozen other candidates on the dais, cannabis provides an opportunity for its proponents – and indeed its opponents – to distinguish themselves.

And yet candidates’ positions on cannabis has gone largely unstudied by public policy groups and overlooked by the mass media. Having identified that gap, VPR Brands, LC, sponsored finance, technology, and public policy writer William Freedman to research and author “The VPR Brands Voters’ Guide to 2020 U.S. Presidential Candidates on Cannabis Issues,” short-named “The VPR Brands Guide”.

Selecting “cannabis” over other terms

Before delving into the methodology, the author would first indicate why he settled on “cannabis” as the term used to describe the substance in question. Certainly, “marijuana” is more widely used and recognized. Until legalization became a mainstream issue, anyone using the term “cannabis” in conversation would be considered ironic by a charitable listener and pedantic by anyone else. Then again, those who use the substance rarely call it “marijuana” either, preferring such slang terms as “pot” or “weed”.

It is the intention of the author and the sponsor to take a serious, academic tone with this study, so the desired level of formality precludes using terms from the vernacular. The decision, then, came down to “marijuana” or “cannabis” or an inelegant switching between the two.

The author settled on cannabis for a number of reasons. First, it is more inclusive, being comprised of kief, hashish, tinctures, oils, and infusions as well as marijuana. Secondly, cannabis is the term favored by physicians, botanists, and other scientists who study its structure and effects.

There is also the suggestion that cannabis is the more time-honored name, while the term “marijuana” – sometimes spelled “marihuana” – was invented in the early 20th century, the point in history when policymakers first felt the need to control the substance. Its etymology is unclear, but it was apparently popularized by Harry J. Anslinger who, in 1930, became the first commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, the predecessor of today’s Drug Enforcement Administration.

Since then, “marijuana” has been the term used primarily by law enforcement officers and has become freighted with a negative connotation as a result. Thus, “cannabis” is the more neutral term and so the one preferred by the author and sponsor of this study.

4. Methodology

The author would be remiss not to indicate two constraints on the validity of the process by which this study was conducted. The first is a time constraint, as the author and sponsor agreed that this report needed to be made public prior to the first Democratic Party debates in late June 2019.

That, however, is of a lesser impact than the main constraint: that of expertise. The author is, and presented himself to the sponsor as, a writer who provides content on topics related primarily to finance and technology, and only secondarily to topics related to public policy. He has a limited background in political science and less in the scientific method.

With that said, he did his best to establish a reasonable methodology to govern this study and endeavored to maintain those guidelines. To some extent, the guidelines had to evolve in an iterative process during the Research phase. This section describes the fully formed methodology.

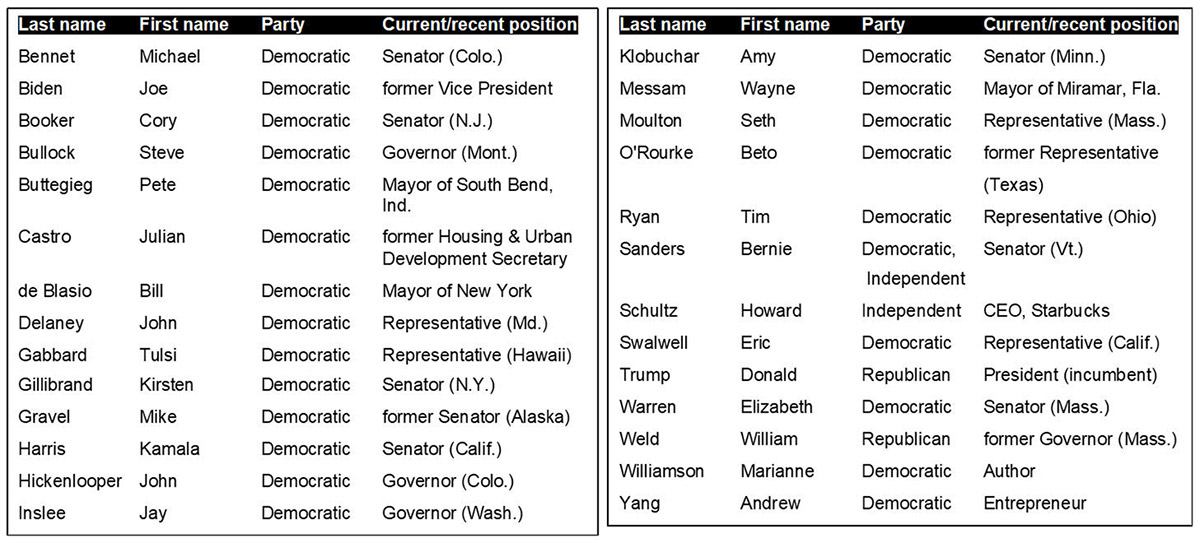

Phase 1: Establish candidate list

The candidates were identified from Ballotpedia, read May 20, 2019 (https://ballotpedia.org/Presidential_candidates,_2020). The author limited the scope to only those candidates who had announced their intentions, filed with the Federal Election Commission, and, in Ballotpedia’s opinion, are likely to reach a nationally broadcast debate stage.

The study’s scope includes 24 candidates running for the Democratic nomination, two running for the Republican nomination, and independent Howard Schultz. The leading alternative parties — Libertarian and Green – had 31 and 14 announced candidates, respectively. Although both these groups are likely to be, each for its own reasons, in favor of a less restrictive national cannabis policy, they have too broad a primary slate to select a standard bearer, so could not feasibly be examined in the VPR Brands Guide.

Phase 2: Establish criteria

The first step in this phase was to limit the scope to an appropriate time period. It is the policy of the VPR Brands Guide that candidates should not be unduly penalized for contrary positions taken while in a role such as a state attorney general – in the case of Kamala Harris, for example – or as a representative of a conservative district – as with Kirsten Gillibrand. Also, in the interest of fairness, it was deemed important to allow candidates time for their positions to evolve. That said, the author did not want to err on the side of equating the record of a candidate who only recently awoke to cannabis issues with another who has taken a longstanding, outspoken leadership role over the course of years. With the intent of balancing these factors, the author arbitrarily set the starting date for considering candidates’ records on January 1, 2015.

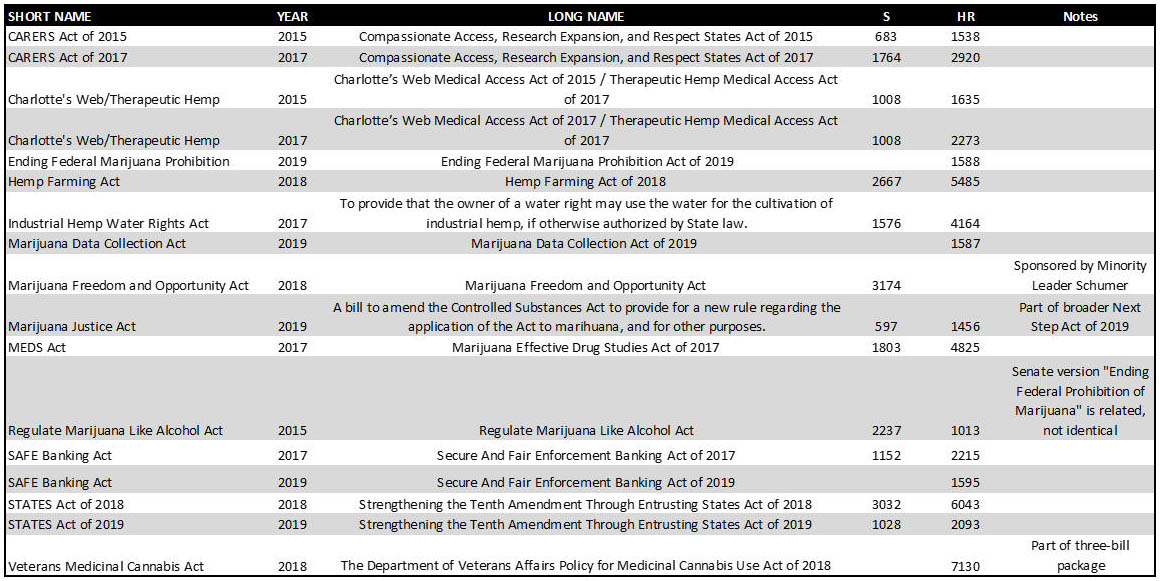

Next, the author determined key cannabis votes taken on Capitol Hill over that time. There were none. Still, there were 17 bills that were introduced, and almost half the candidates were in a position to sponsor or cosponsor the majority of those bills, shown in the following table:

Figure 1: Major federal cannabis bills, 2015-2019

In many instances, identical or nearly identical bills were introduced in two consecutive sessions. The author decided to give each introduction equal weight, because a candidate who repeatedly championed a bill over the course of years ought to be given credit exceeding that given to a candidate who signed on as a cosponsor only after contemplating a presidential run.

Not all bills are considered in this study. The author acknowledges that it is a subjective decision to declare one bill “major” and another not. He further acknowledges that this distinction disadvantages Beto O’Rourke, who sponsored bills that attracted few if any cosponsors or any Senate version.

Roll call or voice votes on funding or omnibus bills for which cannabis issues are minor considerations are not counted. For cannabis-focused bills, no distinction is made between original and subsequent cosponsors.

Legislative positions at the federal level are necessary for analysis such as this but insufficient in itself. Many candidates come from executive positions at the state or municipal level and others come from the private sector; candidates from neither of these subsets were in any position to sponsor or cosponsor resolutions in the U.S. Senate or House of Representatives. Further, many senators and members of Congress have shown leadership on this issue beyond their legislative records, and ought rightly to be given credit for their efforts. Thus, such actions as public speeches, social media signal boosting, letters to Executive Branch policymakers opposing cannabis legalization, and other direct actions are counted.

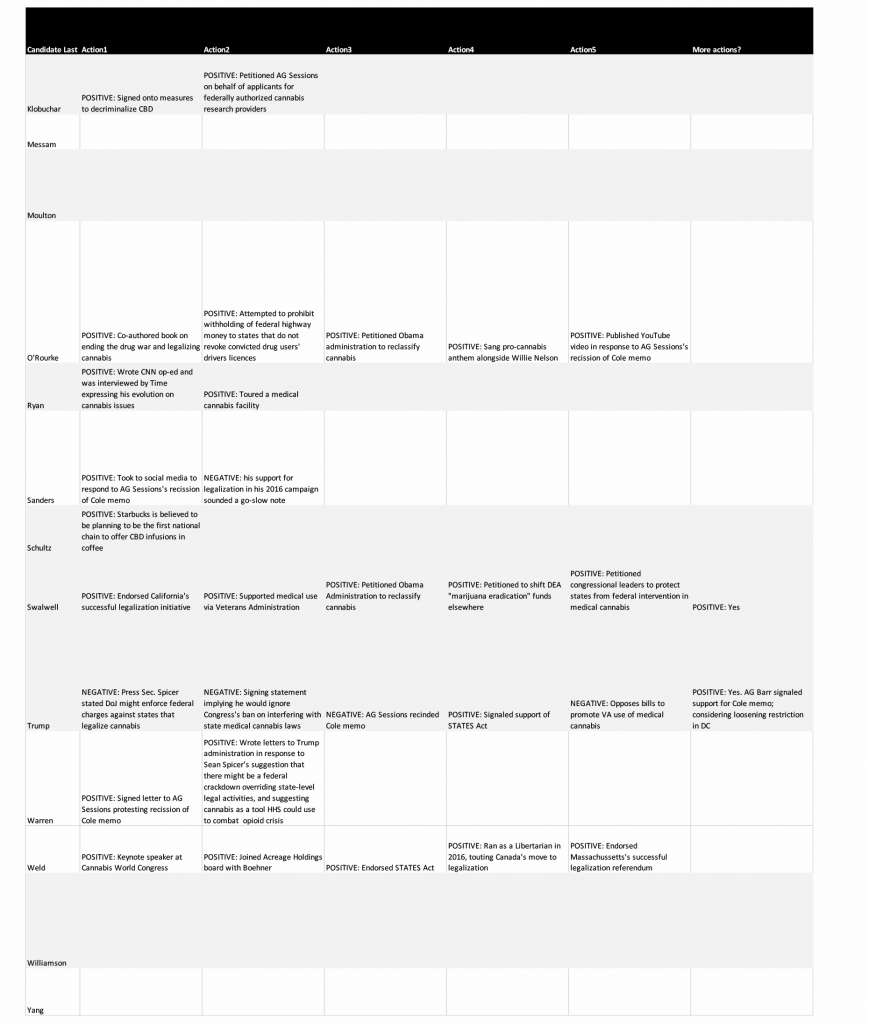

While there was a manageable number of specific congressional bills to include, such was not the case for other actions. The author decided to credit up to five noteworthy actions taken by each candidate since January 1, 2015, and further note if the candidate’s total number of noteworthy actions exceeded five. A series of related actions, an array of similarly worded letters to various individual recipients, for example, can be construed as a single action. However, a privately voiced opinion without policy implications is not counted.

The author also selected six issues under the aegis of “cannabis” to determine the structure of each candidate’s support. Specifically, the candidates were examined for their positions on:

- Medical cannabis,

- Recreational cannabis,

- Industrial hemp,

- Legalization of home-grown plants,

- Prosecution and sentencing reform, and

- Extending financial infrastructure to cannabis firms.

One last criteria considered was the emphasis that each candidate put on their cannabis stance with a rating of 1 to 10, with 1 being avoidance of cannabis as a campaign topic and 10 being a single-issue candidacy focused entirely on cannabis. This turned out to be a highly subjective exercise and the author will accept all reasoned criticism as to his judgment in this regard. He does provide indications of how he came to assign each number below under the Discussion heading.

The author did not consider candidates’ personal experience or lack thereof. One need not have ever indulged in cannabis to support another’s right to indulge, and the history of politics is replete with anecdotes of elected officials who publicly rail against the very vices they pursue privately.

Nor did he consider “electability.” At this stage in 2015, few believed that Donald Trump was electable, and the same could be said for Barack Obama in 2007, George W. Bush in 1999, or Bill Clinton in 1991. While the author harbors private opinions as to which current candidates are floating trial balloons for future election cycles, which ones are auditioning for a vice-presidential role, and which ones are mounting quixotic vanity projects, it is best to acknowledge that these notions exist so that they can be guarded against rather than indulged.

Some candidates have reportedly circulated cannabis-issue petitions in order to build mailing lists; this practice is viewed neither positively nor negatively for current purposes.

As this is the first of what is hoped to be a long series of VPR Brands public policy studies, both the author and the sponsor wanted to establish a tradition that avoids absolutism. Lobbying groups that rank elected officials often penalize them for taking an action that promotes a reasoned, balanced approach to governance if it is contrary to the fortunes of the lobbyists’ constituency. VPR Brands is a small business and seeks to be a good corporate citizen. Thus, this study does not take issue with a candidate’s position or action which could be viewed as sensible limitations on the distribution, sale or legal use of cannabis. The case of John Hickenlooper, as Colorado governor, banning sales to children or limiting the selection of pesticides permitted to be applied to cannabis plants, is instructive. Establishing such rules of the road are viewed neither negatively nor positively in this study.

Similarly, the author was scrupulous not to conflate cannabis positions with those related to opioids, cocaine or other currently illicit substances.

Step 3: Perform Research

The author visited each candidate’s campaign web site and Wikipedia page, then performed a broader web search with candidates’ names plus “cannabis”.

The author and sponsor acknowledge the seminal work done by the news outlet Marijuana Moment (https://www.marijuanamoment.net/). Its candidate-by-candidate breakdown was immensely helpful, and the author felt compelled to make a modest contribution to its Patreon page.

The author was not always successful at avoiding references to other rankings, but the attempt was made and he is confident in the independence of his research and the findings based thereon.

Step 4: Weigh results

For every favorable sponsorship, a candidate is awarded 3 points. For every favorable cosponsorship, a candidate is awarded 2 points. As originally conceived, a favorable vote was worth 1 point, while unfavorable sponsorships, cosponsorships, and votes were worth -3, -2, and -1 point respectively. As data became available, though, these votes and unfavorable legislative actions turned out to be hypothetical. The author decided to keep the point scale intact, though, for ease of comparison to potential studies to come.

Similarly, for each favorable action, a candidate is awarded 1 point, while for each unfavorable action a candidate is awarded -1 point. Unfavorable actions were indeed observed. Further, each Yes-Favorable response to More Actions? Yielded 1 point, while each Yes-Unfavorable response yielded -1 point; each No or Yes-Mixed yielded 0 points. Each favorable position yields 1 point and each unfavorable position yields -1 point.

Points are totaled for each candidate then multiplied by the candidate’s emphasis score.

Although the VPR Brands Guide breaks out unweighted scores for discussion purposes, the official “headline” score for each candidate is the one that factors in the emphasis score.

The author acknowledges that this model skews in favor of senators and members of Congress, who can earn up to a theoretical 51 points based on their legislative record alone, while non-lawmakers can score up to a theoretical 12 – which lawmakers are not prohibited from scoring as well. The author and sponsor welcome informed opinions on how this disparity can be addressed in future VPR Brands guides.

Step 5: Compare results

After independent research is complete, results were compared to analogous results from the most recent scorecards published by the National Association for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML).

5. Analysis

The VPR Brands Guide’s scope was limited to these candidates:

Figure 2: List of candidates

Legislative record

Thirteen candidates were in positions to support federal legislation during the timeframe under consideration. Here are their records on those bills. None of the candidates who served on Capitol Hill during this timeframe took unfavorable positions on any of them, as far as the author could determine.

- Bennet sponsored Industrial Hemp Water Rights Act; he cosponsored CARERS Act of 2015, Charlotte’s Web Act of 2015, Hemp Farming Act, Marijuana Freedom and Opportunity Act, Marijuana Justice Act, SAFE Banking Act of 2017, STATES Act of 2018, and STATES Act of 2019.

- Booker sponsored CARERS Act of 2015, CARERS Act of 2017, and Marijuana Justice Act; he cosponsored SAFE Banking Act of 2017 and STATES Act of 2018.

- Delaney cosponsored Charlotte’s Web Act of 2015, Charlotte’s Web Act of 2017, and SAFE Banking Act of 2017.

- Gabbard sponsored Marijuana Prohibition Act of 2019 and Marijuana Data Collection Act; she cosponsored CARERS Act of 2015, Charlotte’s Web Act of 2015, Hemp Farming Act, Industrial Hemp Water Rights Act, Marijuana Justice Act, SAFE Banking Act of 2017, SAFE Banking Act of 2019, STATES Act of 2018, and Veterans Medical Cannabis Use Act.

- Gillibrand cosponsored CARERS Act of 2015, CARERS Act of 2017, Hemp Farming Act, Marijuana Justice Act, MEDS Act, and SAFE Banking Act of 2017.

- Harris cosponsored Marijuana Justice Act and SAFE Banking Act of 2017.

- Klobuchar cosponsored Charlotte’s Web Act of 2017, MEDS Act, SAFE Banking Act of 2017, STATES Act of 2018, and STATES Act of 2019.

- Moulton sponsored Veterans Medical Cannabis Use Act; he cosponsored CARERS Act of 2015, Marijuana Prohibition Act of 2019, Marijuana Data Collection Act, SAFE Banking Act of 2017, and SAFE Banking Act of 2019.

- O’Rourke cosponsored CARERS Act of 2015, CARERS Act of 2017, Charlotte’s Web Act of 2015, Charlotte’s Web Act of 2017, SAFE Banking Act of 2017, and STATES Act of 2018.

- Ryan cosponsored SAFE Banking Act of 2017, SAFE Banking Act of 2019, STATES Act of 2018, and STATES Act of 2019.

- Sanders sponsored Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol Act; he cosponsored Hemp Farming Act, Marijuana Freedom and Opportunity Act, Marijuana Justice Act, and SAFE Banking Act of 2017.

- Swalwell cosponsored Marijuana Prohibition Act of 2019, Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol Act, SAFE Banking Act of 2017, and SAFE Banking Act of 2019.

- Warren sponsored STATES Act of 2018 and STATES Act of 2019; she cosponsored CARERS Act of 2015, CARERS Act of 2017, Marijuana Freedom and Opportunity Act, Marijuana Justice Act, and SAFE Banking Act of 2017.

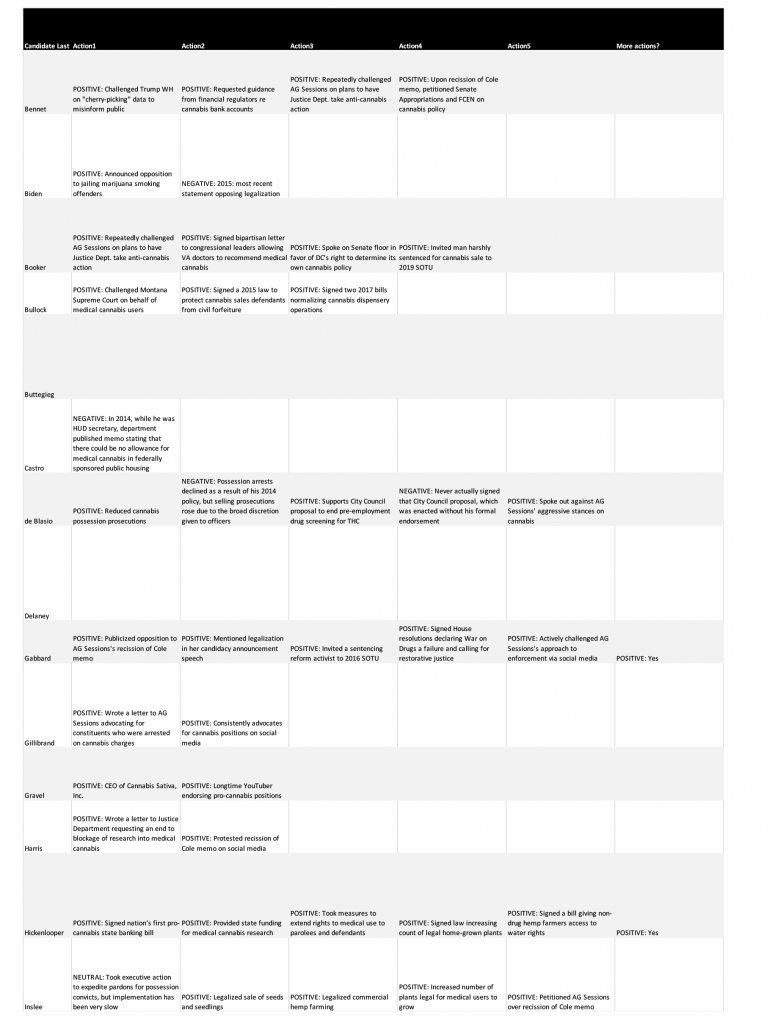

Actions

Non-legislative actions can take many forms and can be attained by any candidate. Some of the most frequently encountered actions observed in this study included:

- Petitioning the Executive Branch over such anti-cannabis actions as the rescission of the Cole memo,

- Writing and publicizing letters to Administration or Congressional leadership in support of constituents who proscribed from receiving medical treatment requiring cannabis,

- Delivering a floor speech in favor of a cannabis issue,

- Inviting an over-sentenced offender of past cannabis laws to the State of the Union address, and

- Repeatedly expressing support for cannabis issues via social media.

This is not an exhaustive list. Details can be found in the VPR Brands Guide’s appendix. It should be noted that many candidates, and perhaps all of them, have taken substantive actions of which the author is unaware, and he apologizes in advance for any omissions and requests comment in case the sponsor sees fit to revise this guide later in the primary season or in advance of the general election.

Further, governors who signed state laws favoring legalization, decriminalization, or normalization of the cannabis issue are given credit here.

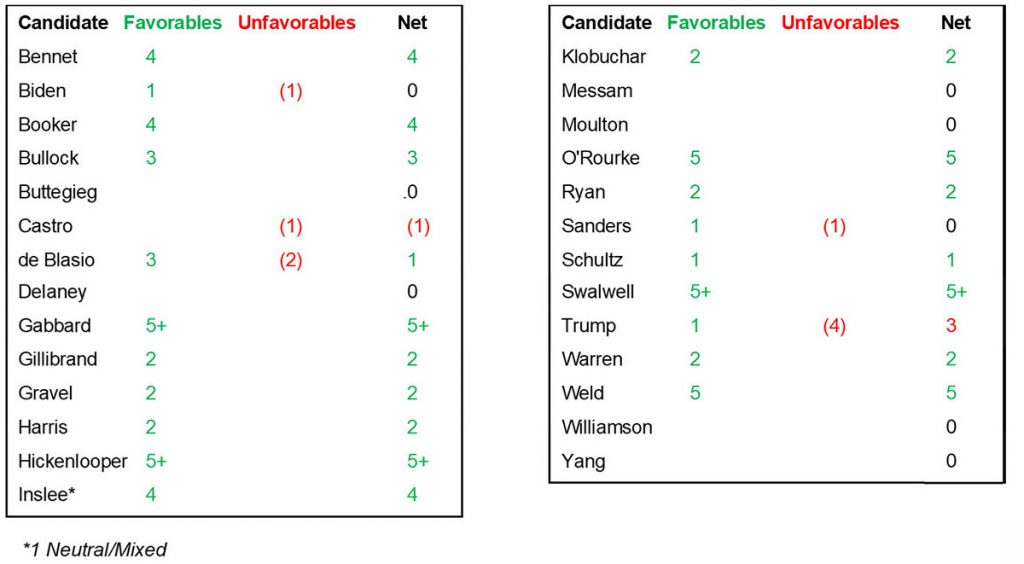

Figure 3: Count of candidates’ actions on cannabis issues

In terms of non-legislative action, then Gabbard, Hickenlooper, and Swalwell appear to be the leaders, with Weld, O’Rourke, Bennet, Booker, and Inslee comprising the next tier. Castro is the only candidate with a net-negative record, although eight of the 27 posted either a neutral or an evenly mixed record. Surprisingly, this includes Sanders, who has been a reliable steward of cannabis legislation in the Senate.

Position statements

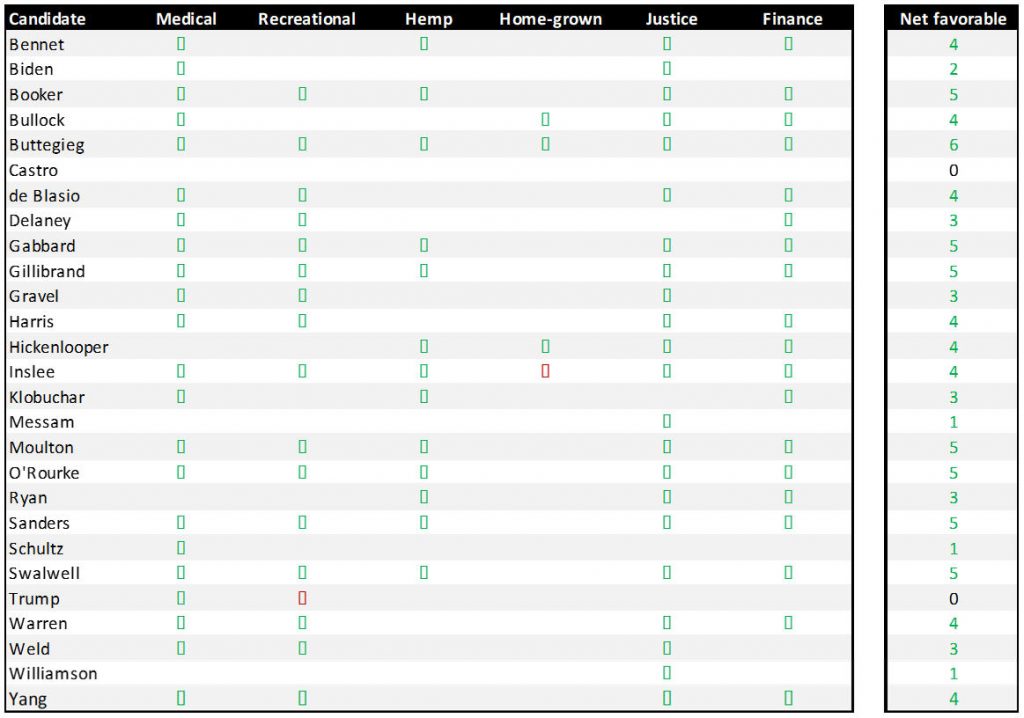

The VPR Brands Guide also rates candidates based on their stated positions on the issues, as this grid indicates:

Figure 4: Candidates’ stated positions on cannabis issues

Although no candidate was a net-negative on cannabis issues, Castro is unique in never having stated any position on any major concern of cannabis voters. Trump has come down on both sides, depending on whether the topic was medical or recreational use, and his support is shown to be a wash.

The only candidate to have declared favorable positions on each of these concerns was Buttegieg, which contrasts sharply with his absence of direct action on any of them. Eight candidates have made public statements favoring five of the topics; this includes Inslee, who has taken stands on all six but his position on the legality of home-grown cannabis is unfavorable.

Emphasis

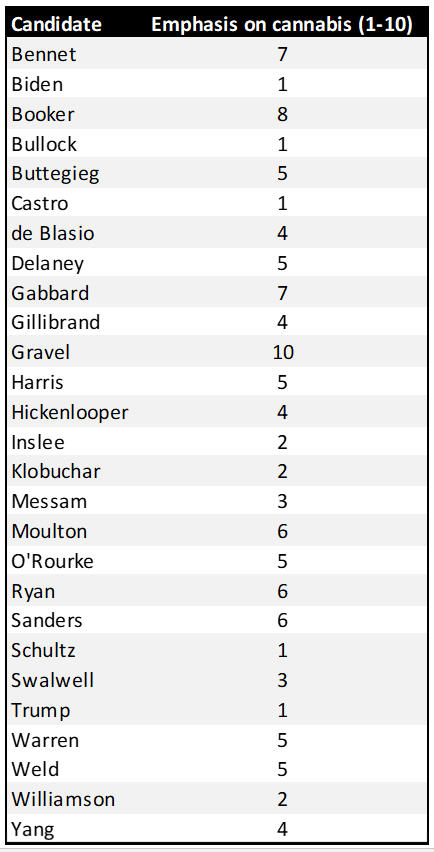

The following table presents the author’s sense of how intensely the candidate is pursuing a hypothetical single-issue cannabis voter on either side of the issue.

Figure 5: Candidates’ emphasis on cannabis issues

Gravel, who is CEO of a cannabis company, is as close to a single-issue candidate as this election cycle has seen. Bennet, Booker, and Gabbard appear to be unequivocally committed to cannabis legalization and normalization; still, their campaigns are presenting these stances as part of broader agendas.

Biden, Bullock, Castro, Schultz, and Trump, meanwhile, appear to be doing all they can to avoid addressing cannabis as a campaign issue. Biden, Castro, and Trump clearly have anti-cannabis stances in their recent histories, but Bullock’s and Schultz’s reticence is surprising. As the governor of a western state, Bullock has seen how successful his neighbors have been as laboratories of pro-cannabis public policy, and has personally taken some significant actions on behalf of users in Montana. Schultz, to be fair, is still playing coy in terms of whether or not he is actually going to campaign full-time for the presidency. Still, as CEO of Starbuck’s, he is possibly more likely than any other individual in the United States to benefit financially from unrestricted federal legalization of CBD.

1. Findings and rankings

In this section of the VPR Brands Guide, the raw scores will be presented first, then they will be weighted by emphasis to provide the headline rankings.

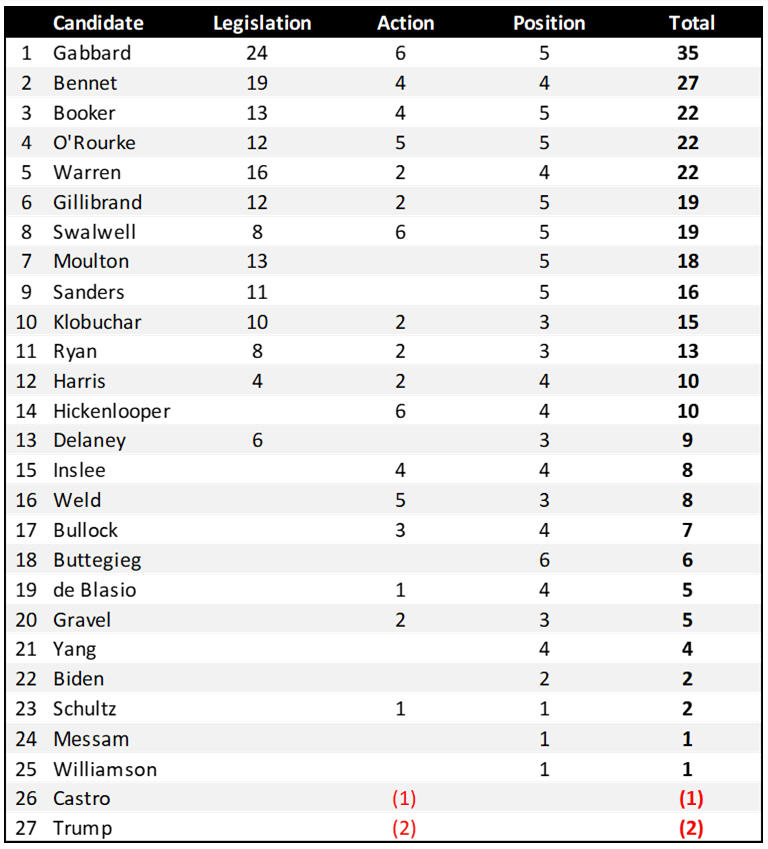

By record

The following table summarizes how many points each candidate scored for their legislative record, actions, and position statements. It then tallies them and ranks candidates accordingly.

Figure 6: Raw measure of candidates’ cannabis advocacy

By this raw measure, Gabbard takes a commanding lead among all candidates in terms of what she has done to promote the legalization and normalization of cannabis. Her score is 30% higher than that of Bennet, who is clearly the second-place alternative. Booker, O’Rourke and Warren are also in contention for the cannabis vote.

As predicted, the emphasis on legislative action inherent in the scoring mechanism favored current and recent senators and members of Congress. Among non-lawmakers, Hickenlooper leads, with Inslee, Weld, and Bullock – all current or former governors of states with progressive cannabis policies – with strong showings.

Castro and Trump are net-negative by this same measure, but not strenuously so.

The surprising aspect of this chart centers on Moulton and Sanders, reliable pro-cannabis votes in the House and Senate respectively. Despite their legislative leadership and firmly stated positions, neither has taken significant action on the issue away from their work on the Hill.

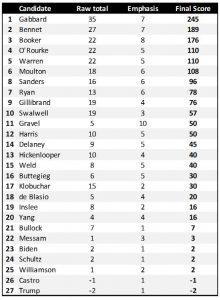

Weighted score

The other metric considered is the degree of emphasis presented in Figure 5. By applying that figure as a multiple, to the Figure 6 totals, the VPR Brands Guide provides the headline candidate rankings, as presented in the following table.

Figure 7: VPN Guide headline ranking

Ultimately, Gabbard retains her spot atop the league table, as she and nearest rival Bennet have identical emphasis weightings. Booker closes the gap, though, by dint of more strenuously advocating for cannabis reform on the campaign trail. O’Rourke, Warren, Moulton, and Sanders comprise the second tier.

By downplaying his strong pro-cannabis voting record, Swalwell barely beats out single-issue candidate Gravel on the final rankings. Adjusted for emphasis, Gravel becomes the most pro-cannabis candidate among the non-lawmakers, although Hickenlooper and Weld are also strong contenders at that level.

1. Discussion

What follows is the author’s notes on how the emphasis scores were arrived at. It also provides some historical context of how the candidates came by their positions.

Bennet opposed Colorado’s legalization referendum in 2012 but has since changed position. Deemphasizing support for recreational use, he focuses on hemp, states’ right to legalize or decriminalize, and cannabis finance.

As Senate Judiciary Committee chairman, Biden was an outspoken proponent of the War on Drugs and on-record up to at least 2014 as being anti-legalization. He now favors reclassifying cannabis to Schedule 2. Biden never mentions cannabis on websites or social media.

For Booker, support for ending the War on Drugs dates back to at least his tenure as Newark mayor. A 2014 statement that he would not commit to full legalization has been mooted by positions and actions taken since 2017.

Bullock worked to overturn a medical cannabis referendum which he argued was being abused. His views on the issue have since evolved.

Buttegieg couches his support for cannabis in terms of racial equality and criminal justice reform, but states clear support for legalization on his campaign website. As South Bend mayor, he signed an anti-cannabinoid ordinance, claiming synthetics were “much more dangerous than actual marijuana”.

Still triangulating on a cannabis position, Castro still presents very little track record from which to infer positions. He apparently favors states’ right to legalize.

Di Blasio is perhaps the most difficult candidate to read on this issue. He favors legalization in New York City, but did not publicize that position until December 2018, when he was clearly considering a presidential run and after Gov. Andrew Cuomo came out in favor. It would be naïve to ascribe any deep-seated convictions to this candidate, at least on this issue.

Delaney is A-rated simultaneously by both National Association of Police Organizations and Americans for Safe Access. While supportive of legalization, he mentions this on his web site only in regards to his “Commitment to Black America”. He offers a record of reliable support but little leadership on cannabis issues.

Gabbard is a full-throated proponent of legalization. Still, she remains more focused on foreign affairs and defense issues.

Gillibrand’s position shifted when she moved from representing a conservative district in the House to represent a liberal state in the Senate. While firmly on the record favoring legalization, she describes her support in terms of class and racial justice while focusing her attention on her pro-choice, family leave and anti-domestic abuse stances. After the VPR Brands Guide’s research phase ended, Gillibrand published a blog post expounding on her pro-cannabis position; this occurred too late in the process to be reflected in the quantitative analysis, but this might mark an inflection point in her emphasis rating and the author would be remiss not to make mention of this action as the final draft is being written.

Gravel is the closest to a pure-play cannabis candidate in the race, judging by his campaign website. He is a decades-long advocate of decriminalization and currently CEO of a cannabis company.

Harris opposed California’s legalization in 2010 and was known as a hard-charging state attorney general, but her views have softened and she has been a dependable supporter of pro-cannabis causes since 2015.

Initially opposed to legalization as Denver mayor and Colorado governor, Hickenlooper had often set aside his personal views to honor the will of the voters. He restricted the sale of edibles in shapes that could entice children and ordered an investigation of pesticide use.

Initially opposed to legalization as Washington governor, Inslee is another candidate whose views have recently evolved, and his record is that of an executive who honors the will of the voters. He pursues actions to restrict use by minors. Under his administration, home cultivation remains illegal in Washington for recreational users.

Klobuchar has emerged as a dependable vote on the periphery of cannabis issues, particularly those relating to CBD, medical use and financing. She was sharply anti-legalization as a prosecutor.

Messam is an outspoken critic of the War on Drugs. He favors federal recognition of states’ rights to legalize.

Moulton supports legalization as a criminal justice reform issue and is particularly sensitive to providing access to medical cannabis via Veterans Administration healthcare outlets.

O’Rourke is the only 2020 candidate open to legalizing narcotics. His 2016 Senate bid was endorsed by NORML, and he sponsored or cosponsored several positive bills, but many were too brief or untargeted or unsupported to be rated here. His history of cannabis support dates back to his El Paso City Council term. Despite unabashed, long-time support for cannabis, he brings it up less and less often as the current campaign continues.

A longstanding cannabis proponent, Ryan is new to taking lead on the issue.

His views have shifted since the early 1990s, but Sanders has been solidly pro-cannabis since at least 1998. He does not back away from his support in the 2020 campaign, but there is an array of other issues that he sees as more important to emphasize.

Schultz’s paperwork is filed with the FEC but he might not run. His candidacy is on hold and will depend on whom the Democrats nominate. If they select a moderate – leading contenders are Biden and Harris – then it is unlikely Schultz will get in the race. If they select a progressive – leading contenders are Sanders and Warren – then his independent candidacy could complicate the entire dynamic.

Swalwell put out a press release as early as 2013 stating his support for legalization, but still has not touted his support in the 2020 campaign.

As on other issues, Trump is unpredictable on this one. His first attorney general was anti-cannabis but his current one is not. The president has signaled support for medical cannabis, but not through the VA. He supports the STATES Act but it has not hit his desk yet, prompting The Hill to speculate about a surprise pro-cannabis announcement late in the campaign.

Warren does not back away from her pro-cannabis position in the 2020 campaign, but there are an array of other issues that she sees as more important to emphasize. Her views changed over time, having run against a pro-legalization candidate in 2013.

Weld has evolved on this issue since working for Ronald Reagan’s Justice Department, where he served as prosecutor for many high-profile DEA cases. Since then, though, he has been at odds with Republican establishment regarding cannabis legalization.

Williamson has a scant record, although she is reportedly in favor of legalization. Without endorsing a position on cannabis, she once told a crowd that it was not worth worrying about when compared to opioids. She once tweeted that cannabis ought to be regulated similarly to alcohol.

Yang deemphasizes his broad support for cannabis and narcotics — but not cocaine — in favor of his signature issue, universal basic income.

1. Comparison to NORML scorecards

Using a long-established methodology, NORML “grades” policymakers on an A-through-F scale. Most recent federal legislators’ grades available are from 2016.

Among senators, NORML rates Sanders A+; Bennet, Booker, and Gillibrand B+; Warren B; and Klobuchar D. Harris is still fairly new to Washington and has not yet been rated.

There is clearly daylight between NORML’s senatorial findings and those of the VPR Brands Guide. Some of that might have to do with the time lag between when the two studies were conducted. The current work suggests that Sanders’s leadership on this issue has been on the wane and, if he ever deserved an A+ on cannabis issues, he might have settled into more of an A or A- range. At the other extreme, Klobuchar might not be the cannabis user’s most full-throated advocate, but her recent record surely rates higher than a barely passing grade.

In the House, NORML rates Swalwell A; Gabbard and O’Rourke B+; and Delaney, Moulton, and Ryan B. The author is comfortable with the premise that, over the past three years, Swalwell has ceded leadership on this issue and Gabbard has stepped up.

NORML also examined governors in 2017. It rated Inslee A and Bullock B. Hickenlooper and Weld had already left office. These ratings appear to mesh with current findings.

2. Conclusion

Americans are not likely to continue to tolerate the status quo of cannabis regulation at the federal level. No matter who is elected, the agenda of legalizing and normalizing the cannabis industry is not under threat. It is a matter of emphasis, nuance, and the speed at which the culture moves forward on this issue.

That said, the two current front-runners, Biden and Trump, are also two of the slowest-going on this issue. Gabbard, Bennet, and Booker are the candidates who are most unabashed in their political support. O’Rourke, Warren, Moulton, and Sanders would also be acceptable candidates for the single-issue cannabis voter. Among non-legislators, Gravel, Hickenlooper, and Weld would also be likely to serve that constituency well.

Neither the author nor the sponsor are advocating that the reader cast their votes on a single issue. This is an academic exercise designed to reveal what each candidate has already done for cannabis users and what they are likely to do if elected to high office.

Still, a matchup between Gabbard and Weld – and perhaps Schultz if, over the course of the campaign, he becomes the world’s leading CBD merchant – would prove to be an intriguing contest.

3. About the author

William Freedman writes frequently on financial topics for Global Finance magazine, and on technology, retirement planning, and economic history for other clients. He has also written on such public policy subjects as universal basic income and drug price transparency. He holds an MBA from The American University, Washington, D.C., and now lives in Jersey City, N.J. He can be contacted via Twitter @WilliamFreedman.

4. About the sponsor

VPR Brands is a technology company whose assets include U.S. and Chinese patents for atomization-related products including technology for medical marijuana vaporizers as well as e-cigarette products and components. Headquartered in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., the company also develops such vaping products as e-liquids, vaporizers, and e-cigarettes.